Trinity Sunday

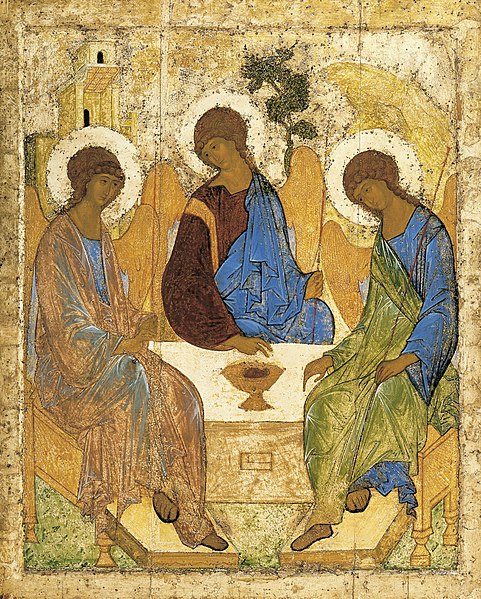

This Trinity Sunday, Deacon D'Paiva mentioned one of the most famous pieces of art depicting the Trinity. An Icon, created by Anton Rublev, a rich symbolism sits behind this piece of art. From the EWTN website (https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/andrei-rublevs-trinity-icon-10158):

Andrei Rublev's Trinity Icon

Andrei Rublev's Trinity Icon

Christopher Evan Longhurst*

Russian Orthodox Trinitarian theology in its most famous artistic expression

The doctrine of the Holy Trinity is commonly expressed in Christian art, particularly in the Western tradition, as God the Father with a grey beard, Jesus the Son in his bosom and a dove hovering overhead. El Greco's mannerist version [1577, Prado Museum, Spain] is among the finest examples. Besides this figurative personification there is a complex theology that renders the Trinity in a rare iconography seen superlatively in Andrei Rublev's icon Trinity [c. 1400 Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow]. In addition to being one of the highest achievements of Russian art, Rublev's icon — also known as "Old Testament Trinity"— portrays a profound theological meaning of the unity of Persons in the Trinity along with the spiritual nature of God's Divine Essence by depicting the Triune God as simply three angels.

Many outside the Russian Orthodox tradition wonder what it is about this image that represents the Trinity. Rublev's subject matter is certainly uncharacteristic of Western Trinity representations. Rather than depicting the classic Father, Son and Holy Spirit breakdown as old bearded man, Jesus and the dove,

Rublev's Trinity displays a rare arrangement of three angels symbolizing a solemn visual Trinitarian theology that conforms to the Russian Orthodox tradition. The Russian Orthodox Church never fully resolved the iconoclastic controversy until 1667. Although debates regarding the legitimacy of representing God in art were more or less settled by the Second Council of Nicaea (787), the Russian Orthodox still found portraying the Father as problematic. Although the Council declared that since the Son became incarnate, depicting Jesus was allowed, the Russian situation regarding the Father remained unclear due to other underlying theological issues. Debates continued among the Orthodox Churches and divergent views emerged with the Coptics prohibiting figurative portrayals of the Father though allowing His conceptual image through abstract illustration. The Syrians, Armenians and Indians followed suit while the Ethiopians allowed the depiction of the Holy Trinity as three distinct Persons. Figurative representation of the Father remained controversial among the Russians until after nearly nine hundred years of debates the Great Synod of Moscow (1667) finally made up the Russians' minds and outlawed all illustrations of the Father in human form. The Synod held that since only God the Son assumed visible human form, the rationale behind sanctioning icons would be limited to depicting figuratively the Second Person of the Trinity only:

It is most absurd and improper to depict in icons God the Father with a grey beard and the Only-Begotten Son in His bosom with a dove between them, because no-one has seen the Father according to His Divinity, and the Father has no flesh [...] and the Holy Spirit is not in essence a dove, but in essence God. (2 § 44)

The Russian Fathers proclaimed: "Those who have intelligence will not depict the Holy Spirit in the likeness of a dove, for on Mount Tabor, He appeared as a cloud and, at another time, in other ways (ibid.).

The Synod stressed that the function of all sacred art would be spiritual mediation through holy and venerated images created only under divine inspiration. Consequently the Russians chose to focus on the so-called "Old Testament Trinity" as the standard representation of the Triune God. Rublev's Trinity icon is a product of this tradition and it became the preferred style replacing all anthropomorphic artistic representations of the Trinity common in Russia at that time.

Rublev's masterpiece attests to the Russian Synod's position by portraying three quasi-identical angels at Abraham's house by the oak of Mamre (cf. Gen 18:1-15). The theological finesse of the work draws attention to the unity of the three Divine Persons in One God. By using the same figures to represent each Divine Person Rublev has emphasized their equality while symbolizing the tri-unity of all three Persons and underscoring the undifferentiated Divine Essence. He has effectively illustrated that God is One Divine Being comprising Three Divine Persons — not one Person with three attributes.

The similitude among the angels recalls the doctrine of the Trinitarian Perichoresis which aids in understanding the Christian notion of three Persons in one another. This circumincession as the Latin Fathers call it, augments the Church's teaching on the notion of Divine Unity and Oneness. In fact, the fundamental basis of the Trinitarian Perichoresis is that there is one God Who is altogether Father, Son and Holy Spirit while distinctions between the Persons and the Divine Essence exist only virtually — a doctrine in the foreground of the Christian faith.

The suitability of Rublev's image for the Russian Orthodox is heightened by the fact that angels are spiritual substances. The entire iconoclastic controversy revolved around God's Divine Nature as an uncreated non-corporeal substance, hence non-representable.

Given its profound theological significances Rublev's Trinity is not only an unsurpassed work of Russian iconography, it is also a first-class figurative "theology of the Trinity". It instructs the faithful and nonbelievers alike that the revelation of the triune God is one of unity in Divine Essence and trinity in Divine Personhood. Given its rich theological symbolism it is not surprising that the Roman Church has established this image as the model for explaining Trinitarian doctrine and inspiring devotion towards the mystery of the inner life of God.

The depiction of the Trinity as three identical figures remains rare in Christian art given that theology ascribes to each Divine Person distinct attributes, namely, to the Father, creation; to the Son, redemption, and to the Holy Spirit, sanctification. Rublev's icon is, however, more precise in expressing the concept of a God who is in Essence one and in Persons three. It illustrates the Church's term for the numerical Unity of God's Essence — (cf. Nicaea I, 325 AD) which seeks to explain the doctrine of the Trinity and reaffirm the principle of the Father and Son as "of one being" (or consubstantialem). This is the essence of Trinitarian theology and also the mystery of the internal life of God.

While the representation of God the Father remains a sensitive issue in the art of Eastern Orthodoxy, Rublev's icon is the unparalleled expression of Trinitarian theology for all Christian Churches throughout the world. It is, in fact, the axial image of Christian unity in theology concerning the doctrine of the Holy Trinity and this is what the Church's feast of 3 June seeks to commemorate.

*Doctor of Sacred Theology

Taken from:

L'Osservatore Romano

Weekly Edition in English

6 June 2012, page 20